By Ken Kaye, Sun Sentinel

2:32 PM EDT, April 5, 2014

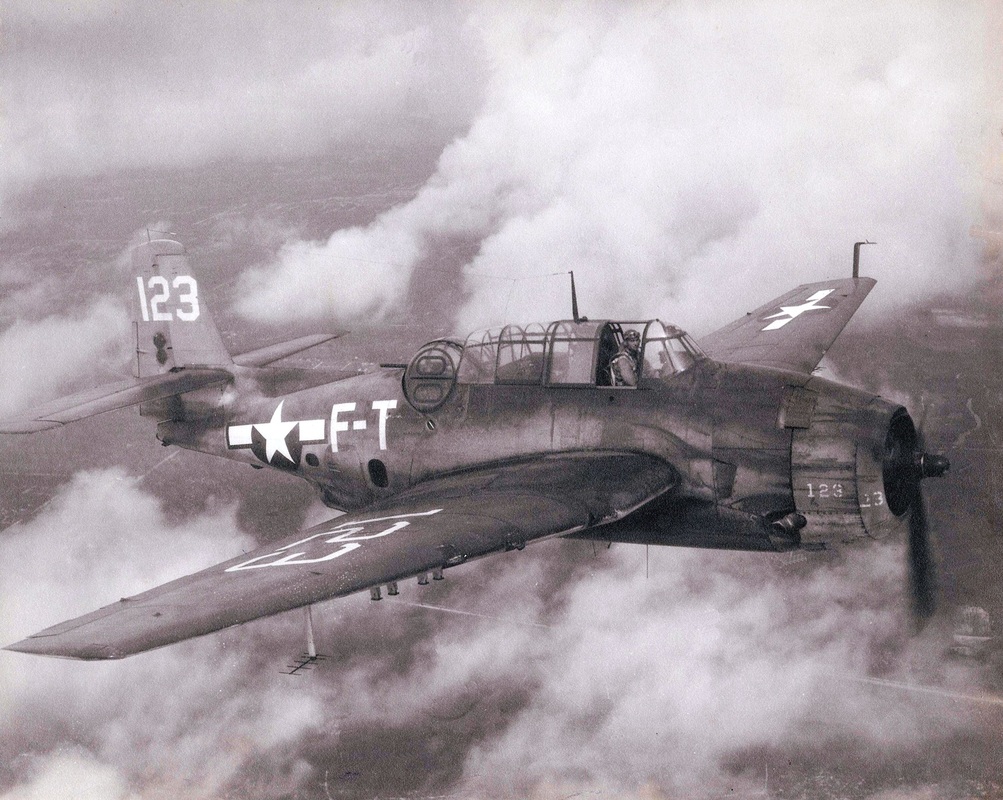

When five Navy torpedo bombers took off from Fort Lauderdale in December 1945 and failed to return, they created one of the greatest aviation mysteries of all time and popularized the myth of the Bermuda Triangle.

Now two aviation sleuths, who have spent more than 25 years trying to crack the case, have a compelling new theory: They believe that a torpedo bomber discovered in western Broward County in 1989 belonged to the lead pilot of Flight 19 and that some of the other planes also crashed on land.

"The circumstantial evidence we've amassed is pretty conclusive," said Jon Myhre, a former Palm Beach International Airport controller. "Nobody had connected the dots before."

Without knowing each other, the two men independently studied the "Lost Patrol" from various angles to calculate where the planes might have gone down while on a routine training mission.

Myhre, of Sebastian, wrote a book, Discovery of Flight 19, about his investigation. After reading it, Andy Marocco, the other enthusiast, called Myhre, and they began collaborating.

"It all started falling right in line," Marocco said.

Marocco, a California businessman, was the one who discovered new information that might break open the 68-year-old mystery. He went to the National Archives and obtained the Navy's 500-page "Board of Investigation Report on the loss of Flight 19."

In it, he found that the USS Solomons aircraft carrier, while off the coast of Daytona Beach, picked up a radar signal from four to six unidentified planes over North Florida, about 20 miles northwest of Flagler Beach.

That was at 7 p.m. on Dec. 5 1945, or about an hour and half after Flight 19 was due back at Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale — today, Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport.

While at an altitude of about 4,000 feet and flying about 135 mph, the planes then made a turn to a compass heading of 170 degrees, or southeast, important details never before been factored into the Flight 19 disappearance, the two men said.

Based on the southeast course, Myhre and Marocco recalculated that at least one of the single-engine, eight-ton planes would have crashed within miles of where the torpedo bomber was found 25 years ago.

That wreckage was spotted by a Broward Sheriff's helicopter pilot in the Everglades about 10 miles west of the Alligator Alley toll booth and about one mile north of the highway.

At the time, several experts, including Myhre, concluded the plane could not have come from Flight 19 because it was too far from where the Navy had received its last vague fix on the squadron, about 150 miles east of Daytona Beach, over the Atlantic.

Myhre and Marocco now say it's fully possible the USS Solomons was tracking the Lost Patrol. Because it was night and there was bad weather, the pilots probably had no idea they had meandered over land, Marocco said.

To bolster their case, they checked photos of the cockpit of the 1989 plane and determined it was a TBM Avenger-3, the exact model flown by Lt. Charles Taylor, the commander of Flight 19.

From an Internet search, they say a rubber heel found at the wreckage site came from a size 11 or 12 dress shoe that would fit a man at least 6 feet tall. "Charles Taylor was 6-foot-1," Marocco said.

Meanwhile, the Navy has no record of a TBM-3 Avenger missing in or around Florida between 1944 and 1952 — other than Charles Taylor's plane from Flight 19 — further leaving open the possibility the Everglades wreck belonged to Flight 19.

Until now, most military and history buffs believed the 14 crew members of Flight 19 perished when their planes ran out of fuel and crashed in the Atlantic.

Because the planes disappeared without a trace, Flight 19 bolstered the myth of the Bermuda Triangle, the area between Miami, Puerto Rico and Bermuda, where hundreds of planes and ships have purportedly vanished.

To confirm their theory on the Lost Patrol, the two men need to re-inspect the plane in the Everglades and find Navy bureau numbers on its wings that would match up with those on Taylor's torpedo bomber.

The problem is they can't find the wreckage.

They fear hunters, air boaters or others who roam Everglades may have taken pieces of the wreckage as souvenirs, particularly after its discovery was publicized in 1989. Still, they hope someone with an interest in digging up history will help them financially to mount an expedition.

"To this day we still can't find an exact location," Marocco said. "But if we find that plane again, I think we'll be able to positively identify it."

What happened to the other planes? Marocco thinks they scattered in different directions — while over Florida — in hopes they would pick up a homing signal to either an aircraft carrier or an airport. He noted two of the planes were flown by Navy crews, three by Marine crews.

"I think they scattered, based on their allegiance to their military unit," Marocco said. "The three Marine planes went toward the Gulf of Mexico and the two Navy planes went south. I think they all ran out of fuel and crashed."

Myhre and Marocco say to this point, the Navy has been of little help in determining whether the Everglades plane was part of Flight 19.

Paul Taylor, spokesman for the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C., said the Navy needs more information.

"We're open to hearing more about the theory and welcome the gentlemen to forward their findings to us for closer examination," he said.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed